Why Obamacare Supporters Won’t Enroll in Obamacare

Today, the beginning of Obamacare’s fourth open enrollment period, will see Obama administration officials and liberal advocates engaging in the usual publicity blitz. They’ll tell Americans how much money they can save, how affordable plans are—don’t believe the hype about premium increases, they claim—and the benefits of having health coverage.

All of this can be rebutted by one simple rejoinder: If these exchange plans are so good, why haven’t you purchased one?

It’s a question I’ve asked several Obamacare advocates, because, while they talk about Obamacare, I actually have to live it. Because Washington DC abolished its private insurance market, I as a small business owner have to buy a plan on the federal exchange. For 2017, new plan requirements by the DC exchange—insurers now have to offer eight “standardized” plans—coupled with the difficult business environment meant that my insurer, CareFirst Blue Cross, cancelled its health savings account plan.

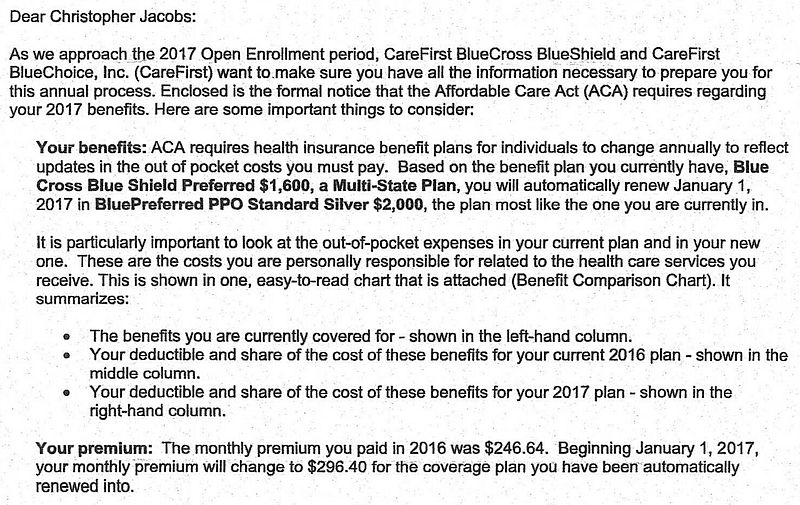

As a result, I and 6,980 other HSA plan participants received cancellation notices in September. As you can see from the notice, the “substitute” plan I was offered has a premium of $296.40—that’s a 20.2 percent increase, for those of you keeping score at home—and a 25 percent increase in my deductible, from $1,600 to $2,000.

The day before I received official confirmation of my plan’s cancellation, I attended a briefing on insurance exchanges. I pointed out that, to most people in Washington DC, Obamacare was an abstract idea. Policy-makers at think-tanks, lobbying firms, or in government have high-paying jobs that come with employer-based health coverage, so they really don’t have to worry about whether the exchanges succeed or fail.

I asked the panelists point-blank: You’re speaking about the state of Obamacare’s exchanges, but do you yourself receive coverage through them?

As I had suspected, most admitted they do not. Sabrina Corlette, a Georgetown University researcher, replied that she was a “spoiled academic” who received coverage through her employer. Ironically enough, Corlette’s presentation for the briefing included a slide noting that the exchanges needed to “boost enrollment.” But when asked whether she would enroll in an exchange plan—thereby boosting enrollment—she said she would not. This brings to mind St. Augustine’s famous phrase, “Grant me chastity and continence—but not yet.”

Elites Won’t Join Obamacare’s Ghettoes

One reason why Corlette, and other “spoiled academics” like her, won’t give up their existing coverage is simple: Compared to employer-based insurance, exchange plans—and this is a technical term—suck.

Thanks to Obamacare’s ability to make insurance competition disappear, nearly one in five Americans (19 percent) will have the “choice” of only one insurer on their exchange in 2017. Obamacare’s benefit mandates have forced insurers to narrow networks—three-quarters of all 2017 exchange offerings include no out-of-network coverage—and raise deductibles so high as to render insurance “all but useless” for many.

As I have previously written, Obamacare’s insurance marketplaces could be more accurately described as ghettoes, not exchanges. The median income among all healthcare.gov enrollees is 165 percent of the poverty level, or about $40,000 for a family of four, so enrollees are predominantly low-income, besides sicker than those on the average employer plan. The combination of narrow networks and tightly managed care has zero appeal to the average person with an employer plan—which explains why the liberal elites promoting Obamacare won’t actually enroll themselves.

‘I Do Try to Think about Them’

At the September briefing, Corlette claimed Obamacare was an attempt to “lift the standards for individual market products” to make them more like employer plans—just not enough for her to enroll. (As someone actually on the exchanges, I can attest to a lot of “lift” for my premiums and deductibles; standards and network access, perhaps not as much.)

She then justified her non-participation in the exchanges by claiming that “when I look at these issues, I do try to think about them. You know, if I were an expecting mother who needs prenatal care…what kind of health insurance would I want?”

All of this sounds as empathetic as thinking about and waving at people in a rowboat from the creature comforts of one’s private yacht. Her condescending tone presupposes that, while exchange plans might not totally replicate employer coverage, they’ll pass muster for “them”—not actually good enough for the elites themselves, mind you, but good enough for the unwashed masses who will purchase the plans.