What You Need to Know About Budget Reconciliation in the Senate

After last week’s House passage of the American Health Care Act, the Senate has begun sorting through various policy options for health care legislation. But looming over the policy discussions are procedural concerns unique to the Senate. Herewith a primer on the process under which the upper chamber will consider an Obamacare “repeal-and-replace” bill.

How Will the Bill Come to the Senate Floor?

The bill that passed the House was drafted as a budget reconciliation bill. The phrase “budget reconciliation” refers to a process established by the Congressional Budget Act of 1974, in which congressional committees reconcile spending in programs within their jurisdiction to the budget blueprint passed by Congress. In this case, Congress passed a budget in January that required health-care committees to report legislation reducing the deficit by $1 billion—the intended vehicle for an Obamacare “repeal-and-replace” bill.

What’s So Important about Budget Reconciliation?

Under most circumstances, the Senate can only limit debate and amendments by invoking cloture, which requires the approval of three-fifths of all senators sworn (i.e., 60 votes). Because the reconciliation process prohibits filibusters and unlimited debate, it allows the Senate to pass reconciliation bills with a simple majority (i.e., 51-vote) threshold.

Why Does the ‘Byrd Rule’ Exist as part of Budget Reconciliation?

Named for former Senate Majority Leader Robert Byrd (D-WV), the rule intends to protect the integrity of the legislative filibuster. By allowing only matters integral to the budget reconciliation to pass the Senate with a simple majority (as opposed to the 60-vote threshold), the rule seeks to keep the body’s tradition of extended debate.

What Is the ‘Byrd Rule’?

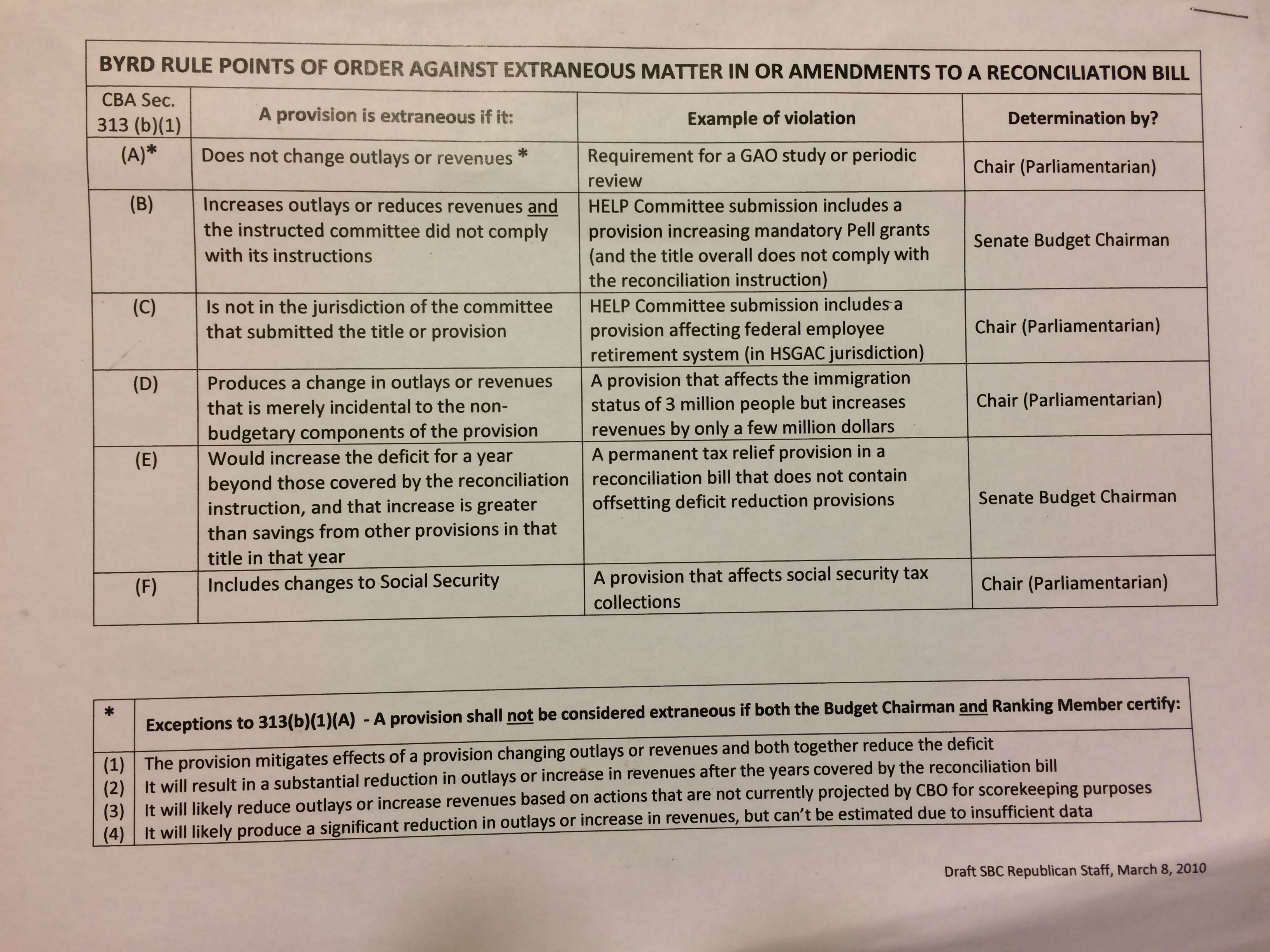

Simply put, the rule prohibits “extraneous” material from intruding in budget reconciliation legislation. However, the term “Byrd rule” is technically a misnomer in two respects. First, the “Byrd rule” is more than just a longstanding practice of the Senate. After several years of operation as a Senate rule, it was codified into law beginning in 1985, and can be found at 2 U.S.C. 644. Second, the rule consists of not just one test to define whether material is “extraneous,” but six.

What Are the Six Different Types of Extraneous Material?

So the Various Types of ‘Byrd Rule’ Violations Are Not Necessarily Equivalent?

Correct. While most reporters focus on the fourth test—when a legislative provision has a budgetary impact merely incidental to the provision’s policy change—that is not the only type of rule violation. Nor in many respects is it the most significant.

While violations of the fourth test are fatal to the provision—the extraneous material is stricken from the underlying legislation—violations of the third (material outside the jurisdiction of committees charged with reporting reconciliation legislation) and sixth (changes to Title II of the Social Security Act) tests are fatal to the entire bill.

Who Determines Whether a Provision Qualifies as ‘Extraneous’ Under the ‘Byrd Rule’?

How Does One Determine Whether a Provision Qualifies as ‘Extraneous’ under the ‘Byrd Rule’?

In some cases, determining compliance with the rule is relatively straight-forward. A provision dealing with veterans’ benefits (within the jurisdiction of the Veterans Affairs Committee) would clearly fail the third test in a tax reconciliation bill, as tax matters lie within the Finance Committee’s jurisdiction.

However, other cases require a more nuanced, textual analysis by the parliamentarian. Such an analysis might examine Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and other outside scores, to assess the provision’s fiscal impact (or lack thereof), the statute the reconciliation bill seeks to amend, other statutes cross-referenced in the legislation (to assess the impact of the programmatic changes the provision would make), and prior precedent on related matters.

When Does the Senate Assess Whether a Provision Qualifies as ‘Extraneous’?

In some respects, assessing compliance is an iterative process. Often, the Senate parliamentarian will provide informal advice to majority staff as they begin to write reconciliation legislation. While these informal conversations help to guide bill writers during the drafting process, the parliamentarian normally notes that these discussions do not constitute a formal advisory opinion; minority party staff and other interested persons are not privy to the ex parte conversations, and could in time bring her new information that could cause her to change her opinion.

Do Debates about the ‘Byrd Rule’ Take Place on the Senate Floor?

They can, and they have, but relatively rarely. As James Wallner, an expert in Senate parliamentary procedure, notes, over the last three decades, the Senate has formally adjudicated only ten instances of the fourth test—whether a provision’s fiscal impacts are merely incidental to its proposed policy changes.

Because most determinations of “Byrd rule” compliance (or non-compliance) have been made through informal, closed-door “Byrd bath” discussions in the Senate parliamentarian’s office, there are few formal precedents—either rulings from the chair or votes by the Senate itself—regarding specific examples of “extraneous” material. As a result, the Senate—whether the parliamentarian, the presiding officer, or the body itself—has significant latitude to interpret the statutory tests about what qualifies as “extraneous.”

Can the Senate Overrule the Parliamentarian about What Qualifies as ‘Extraneous’ Under the ‘Byrd Rule’?

Yes, in two respects. The presiding officer—whether the vice president as president of the Senate, the president pro tempore (currently Sen. Orrin Hatch, R-UT), or another senator—can disregard the parliamentarian’s guidance and issue his or her own ruling. Alternatively, a senator could appeal the chair’s decision, and a simple majority of the body could overrule that decision. There is a long history of senators doing just that.

As a practical matter, however, such a scenario appears unlikely during the Obamacare debate, for two reasons. First, some senators may view such a move as akin to the “nuclear option,” undermining the legislative filibuster by a simple majority vote. The recent letter signed by 61 senators pledging to uphold the legislative filibuster indicates that at least some senators in both parties want to preserve the usual 60-vote margin for passing legislation, and therefore may not wish to set a precedent of allowing potentially “extraneous” material on to a budget reconciliation bill through a simple majority.

Second, if the Senate did overrule the parliamentarian on a procedural matter related to budget reconciliation, a conservative senator would likely introduce a simple, one-line Obamacare repeal bill and ask the Senate to overrule the parliamentarian to allow it to qualify as a reconciliation matter. Since many members of the Senate, like the House, do not actually wish to repeal Obamacare, they would likely decline to head down the road of overruling the parliamentarian, for fear it may head in this direction.

Can the Senate Waive the ‘Byrd Rule’?

Yes—provided three-fifths of senators sworn (i.e., 60 senators) agree. In the past, many budget reconciliation bills—like the Balanced Budget Act of 1997—passed with far more than 60 Senate votes, which made waiving the rule easier.

However, Republicans did not agree to waive the rule for extraneous material included in Senate Democrats’ Obamacare “fix” bill in March 2010. That material was stricken from the legislation and did not make it into law. For this and other reasons, it seems unlikely that eight or more Senate Democrats would vote to waive the rule for an Obamacare “repeal-and-replace” bill.

Didn’t Democrats Pass Obamacare through Budget Reconciliation?

Yes and no. They fixed portions of Obamacare—for instance, the notorious “Cornhusker Kickback”—through a budget reconciliation measure that passed through both houses of Congress in March 2010. But the larger, 2,400-page measure that passed the Senate on Christmas Eve 2009 was enacted into law first.

Once Scott Brown’s election to the Senate in January 2010 gave Republicans 41 votes, Democrats knew they could not go through the usual process of convening a House-Senate conference committee to consider the differences between each chamber’s legislation. A conference report is subject to a filibuster, and Republicans had the votes to sustain that filibuster.

Instead, House Democrats agreed to pass the Senate version of the legislation—the version that passed with 60 votes on Christmas Eve 2009—then have both chambers use a separate budget reconciliation bill—one that could pass the Senate with a 51-vote majority—to make changes to the bill they had just enacted.

This post was originally published at The Federalist.