Does Medicaid Expand Inequality?

Believe it or not, an incredibly powerful article about health policy mentions the word “medical” once only in passing, and “health” not at all. On Thursday, Politico ran a feature article on the University of Michigan, and how it—and many other prominent public universities—face a “crisis of confidence.” In seeking to attract affluent, and frequently out-of-state, students, these institutions have shunned working-class families, many of whom no longer feel welcome, or try to apply.

The crisis of confidence stems largely from public universities’ financial strategies. That’s where health care comes in, in a big way. Medicaid’s constant, inexorable growth in state budgets has left less money for education of all types, not least higher education. As Medicaid spending has risen, state funding of public universities has declined, leading them to raise tuition and increase their percentage of out-of-state students to help balance the books. At the end of this fiscal game of “Musical Chairs,” many children from working-class families can’t find a proverbial seat at a top-tier institution.

Numbers Don’t Lie

A review of state budget expenditure reports puts the effects in stark relief. In fiscal year 1987, Michigan spent 9.7 percent of its state budget on Medicaid, and 8.5 percent on higher education. Nearly three decades later, in fiscal year 2015, Michigan spent a whopping 30.2 percent of its budget on Medicaid, and 4.3 percent on higher education. The state more than tripled the share of the budget devoted to Medicaid, while cutting the share of spending on higher education in half.

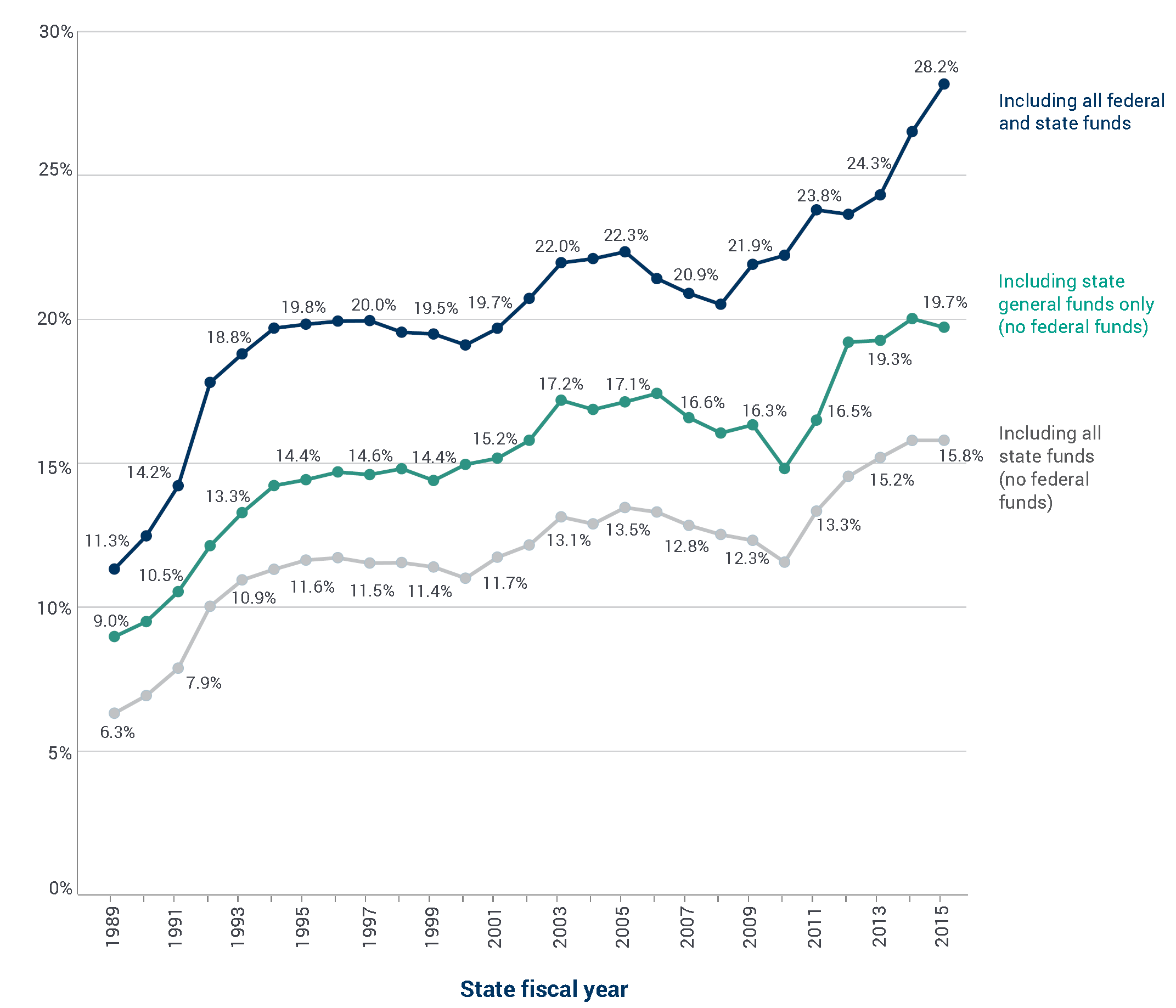

The national spending numbers tell a similar story. In fiscal year 1987, states spent an average of 9.8 percent of their budgets on Medicaid, and 11.1 percent on higher education. In fiscal year 2015, states spent an average of 28.2 percent on Medicaid, and 10.1 percent on higher education. Here again, higher education spending declined, even as Medicaid spending nearly tripled. While in 1987, states spent roughly half as much on Medicaid as they did on primary and secondary education, Medicaid has long since supplanted K-12 education as the top spending item in states’ budgets.

The Medicaid Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC) has a chart showing the way in which Medicaid spending has grown over time. Although their graphic doesn’t include it, one could easily insert two intersecting lines showing how the share of state spending on K-12 education and higher education has declined even as Medicaid spending has risen.

How This Affects Americans

In Michigan, universities have taken it on the chin more than in most states. Primary and secondary education comprise a relatively large percentage of the state’s budget, making the share of spending on post-secondary education (4.3 percent) less than half the national average. Politico explains the effect on the University of Michigan and its students:

In the late 1960s, the state covered 70 percent of instructional costs. By the late 1990s, state support covered less than 10 percent of instructional costs, which were largely unchanged when adjusted for inflation. The trend has persisted. One recent report found that, since 2002, state support for higher education in Michigan has declined 30 percent, when adjusted for inflation.

The university, like nearly every other state school in the nation, leaned on tuition to make up the difference. In-state tuition rose, but university leaders also focused on another, more lucrative, funding stream: out-of-state students, many of them elite students from wealthy families who couldn’t get into the Ivy League. Michigan was the next best thing.

“The university had no choice but to increase out-of-state enrollments of students paying essentially private tuition levels,” [former University of Michigan President James] Duderstadt said. Tuition rose to $14,826 a year for Michigan students; room and board adds about $12,000. In the 1970s, tuition was less than $600 per year. Out-of-state students, who now pay $47,476 per year, make up roughly half of the student body at Michigan, up from 30 percent in the late 1960s.

But as tuition rose, wages stagnated. The median family income in Michigan in 1984 was $50,546, in 2016 dollars. In 2016, it was $57,091. The working class was priced out.

A Poverty Trap?

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has indicated its belief that Medicaid itself discourages work. Specifically, CBO wrote that “expanded Medicaid eligibility under [Obamacare] will, on balance, reduce incentives to work.” Because an extra dollar of income could cause beneficiaries to lose access to Medicaid, costing them hundreds, even thousands, of dollars in insurance premiums and co-payments, some individuals will avoid work to keep their incomes below eligibility caps.

However, few have examined the way in which Medicaid can keep people in poverty not just from its direct effects (i.e., discouraging work), but by its indirect effects—the opportunity cost associated with state spending. Every dollar a state spends on Medicaid represents a dollar not spent on rescuing a student trapped in a failing school, or on scholarships for working-class families to attend top-tier universities.

This post was originally published in The Federalist.