Single Payer’s Road to Rationing

The reintroduction of Democrats’ single-payer legislation has some families contemplating what total government control of the health-care sector would mean for them. Contrary to the rhetoric coming from liberals, some of the families most affected by a single-payer system want nothing to do with this brave new health care world.

As this father realizes, giving bureaucrats the power to deny access to health care could have devastating consequences for some of the most vulnerable Americans.

Determining the ‘Appropriate’ Use of Medical Resources

To summarize the Twitter thread: The father in question has a 12-year-old son with a rare and severe heart condition. Last week, the son received an implantable cardioverter defibrillator to help control cardiac function.

But because the defibrillator is expensive and cardiologists were implanting the device “off-label”—the device isn’t formally approved for use in children, because few children need such a device in the first place—the father feared that, under a single-payer system, future children in his son’s situation wouldn’t get access to the defibrillator needed to keep them alive.

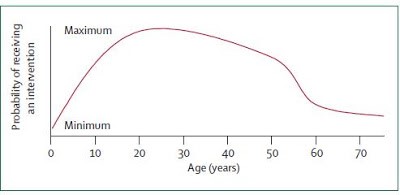

The father has reason to worry. He cited a 2009 article written by Zeke Emanuel—brother of Rahm, and an advisor in the Obama administration during the debate on Obamacare—which included the following chart:

The chart illustrates the “age-based priority for receiving scarce medical interventions under the complete lives system”—the topic of Emanuel’s article. If a picture is worth a thousand words, then this chart sure speaks volumes.

Also consider some of Emanuel’s quotes from the same article, in which he articulates the principles behind the allocation of scarce medical resources:

Adolescents have received substantial education and parental care, investments that will be wasted without a complete life. Infants, by contrast, have not yet received these investments.

The complete lives system discriminates against older people….[However,] age, like income, is a ‘non-medical criterion’ inappropriate for allocation of medical resources.

If those quotes do not give one pause, consider another quote by Zeke Emanuel, this one from a 1996 work: “[Health care] services provided to individuals who are irreversibly prevented from being or becoming participating citizens are not basic and should not be guaranteed. An obvious example is not guaranteeing health services to patients with dementia.” When that quote resurfaced during the debate on Obamacare in 2009, Emanuel attempted to claim he never advocated for this position—but he wrote the words nonetheless.

The Flaw in Centralized Decision-Making

The father in his Twitter thread hit on this very point. Medical device companies have not received Food and Drug Administration approval to implant defibrillators in children in part because so few children need them to begin with, making it difficult to compile the data necessary to prove the devices safe and effective in young people.

Likewise, most clinical trials have historically under-represented women and minorities. The more limited data make it difficult to determine whether a drug or device works better, worse, or the same for these important sub-populations. But if a one-size-fits-all system makes decisions based upon average circumstances, these under-represented groups could suffer.

To put it another way: A single-payer health care system could deny access to a drug or treatment deemed ineffective, based on the results of a clinical trial comprised largely of white males. The system may not even recognize that that same drug or treatment works well for African-American females, let alone adjust its policies in response to such evidence.

A ‘Difficult Democratic Conversation’

The chronically ill and those toward the end of their lives are accounting for potentially 80 percent of the total health care bill out here….There is going to have to be a conversation that is guided by doctors, scientists, ethicists. And then there is going to have to be a very difficult democratic conversation that takes place.

Some would argue that Obama’s mere suggestion of such a conversation hints at his obvious conclusion from it. Instead of having a “difficult democratic conversation” about ways for government bureaucrats deny patients care, such a conversation should center around not giving bureaucrats the right to do so in the first place.

This post was originally published at The Federalist.