Three Things to Know about “Surprise” Medical Bills

In recent months, lawmakers in Washington have focused on “surprise” medical bills. In large part, this term refers to two types of incidents: 1) individuals who received pre-arranged treatment at an in-network hospital, but saw an out-of-network physician (e.g., anesthesiologist) during their stay, or 2) individuals who had to seek care at an out-of-network hospital during a medical emergency.

In both cases, the out-of-network providers can “balance bill” patients—that is, send them an invoice for the difference between an insurer’s in-network payment and what the physician actually charged. Because these bills can become quite substantial, and because patients do not have a meaningful opportunity to consent to the higher charges—many patients never meet their anesthesiologist until the day of surgery, and few people can investigate hospital networks during an ambulance ride to the ER—policy-makers see reason to intervene.

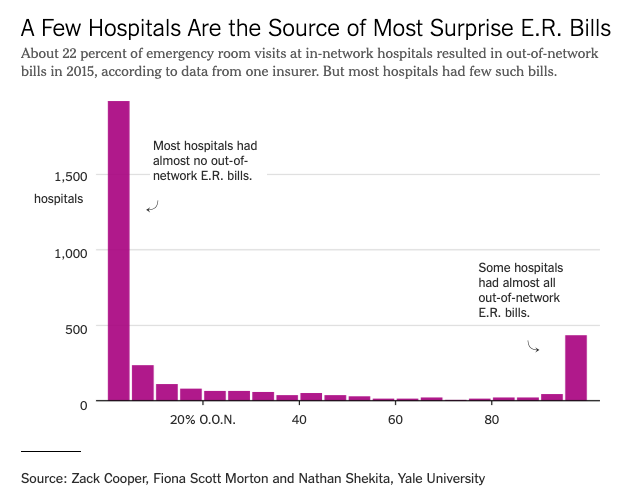

1. Few Hospitals Comprise Most of the ‘Surprise’ Incidents

As a chart from The New York Times demonstrates, most hospitals had zero, or close to zero, out-of-network emergency room bills in 2015, according to a study by three Yale University professors:

“Surprise” bills applied in 22 percent of ER visits, but as a Times reporter noted, they are “not happening to some random set of patients in every hospital. [They’re] happening to a large percentage of patients in certain hospitals.”

As noted above, most hospitals don’t have this problem, because they keep their ER physicians and other doctors in-network. Unfortunately, however, the one-quarter or so of hospitals that have not forced their physicians in-network have made life difficult for the rest of the hospital sector.

The hospital industry should have done a much better job of policing itself and weeded out these “bad actors” years ago. Had they done so, the number of “surprise” bills likely would not have risen to a level where federal lawmakers demand action. However, the fact that these incidents still only occur in a minority of hospitals suggests reason for continued caution—because why should Congress impose a far-reaching solution to a “problem” that doesn’t affect most hospitals?

2. The Federal Government Has Little Reason to Intervene

Over and above the question of whether “surprise” bills warrant a legislative response, lawmakers should also ponder why that response must come from the federal government. Even knowledgeable reporters have (incorrectly) assumed that a solution to the issue must emanate from Washington because only the federal government can address “surprise” bills for self-funded employer plans. Not so.

ERISA, in this case, refers to the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974, which regulates employer-provided health insurance. ERISA states that its provisions “shall supersede any and all state laws insofar as they may now or hereafter relate to any employee benefit plan.”

But as that language indicates, ERISA applies only to the regulation of employee benefit plans—i.e., the employer as an insurer. It does not apply to the regulation of providers—i.e., hospitals, doctors, etc. As a Brookings Institution analyst admitted, states can, for instance, require hospitals to issue an in-network guarantee, ensuring that all doctors at an in-network hospital are considered in-network.

For most of the past year, interest groups have lobbied Congress on “surprise” billing. As one might expect, everyone wants a solution that takes patients out of the line of fire in negotiations between doctors, hospitals, and insurers, but no one wants to take a financial haircut in any solution that emerges.

The lack of agreement on a path forward indicates that Congress should take a back seat to the states, and let them innovate solutions to the issue. Indeed, several states have already enacted legislation on out-of-network bills, suggesting that Congress might do more harm than good by weighing in with its own “solution.”

3. Some Republicans Support Socialistic Price Controls

Both the comparatively isolated nature of the problem and the lack of a clear need for federal involvement suggest that some on the left continue to raise the “surprise” billing issue as part of a larger campaign. By establishing that the federal government should regulate the prices of health-care services—even those in private insurance plans—liberals can lay down a predicate for a single-payer health-care system that would do the exact same thing, just on a larger scale.

Sure enough, congressional Republicans, like Oregon Rep. Greg Walden and Tennessee Sen. Lamar Alexander, have endorsed legislation establishing a statutory cap on prices for out-of-network emergency services. (Remember: In policy-making, bipartisanship only occurs when conservatives agree to liberal policies.)

Both the House Energy and Commerce Committee and Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee have introduced proposals that would engage in such federal price-fixing, although lawmakers recently modified the House bill to allow for binding arbitration between doctors and hospitals where the disputed sums exceed certain thresholds. Alexander wants to move his legislation on the Senate floor within weeks.

Last month, Alexander said he “instinctively” liked the in-network guarantee approach—which requires hospitals to have their physicians in-network, while letting insurers, hospitals, and doctors negotiate those in-network prices without setting them through government fiat. However, he told reporters that he ultimately endorsed the price-fixing approach because the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) called it “the most effective at lowering health care costs.”

The retort to Alexander’s comment seems obvious: Of course, price-fixing will lower health care costs. Indeed, CBO said the price-fixing provision would save by far the greatest amount of money of any section of the nearly 250-page bill, because it “lower[s] payment rates” to physicians.

If Alexander suddenly wants to use price controls to lower health care costs, then why not regulate the prices of all health care services ($129.95 for surgery, anyone?)—or move to full-on single-payer? Because the quality of care will suffer too—as will American patients.

A Spoonful of Socialism, Anyone?

I noted above that the hospital industry caused the “surprise” billing problem in the first place. I have little love for hospital executives, many of whom behave like greedy monopolists, and who represent the single biggest argument for single-payer health care I can think of.

Yet however much hospital executives may have earned opprobrium by their conduct, the American people don’t deserve a single-payer system, with its massive economic disruption and its inferior care, foisted on them. They deserve better than federally imposed price controls as a “solution”—whether as the mere “spoonful of socialism” in the “surprise” billing legislation, or an all-out move to single-payer.

This post was originally published at The Federalist.