Biden Official Who Got Twitter to Censor Alex Berenson Has His Own History of Publishing Misinformation

Pot, meet kettle. Those words accurately describe reactions to the recent publication of documents indicating that former Biden covid advisor Andy Slavitt worked to have writer Alex Berenson banned from Twitter last year.

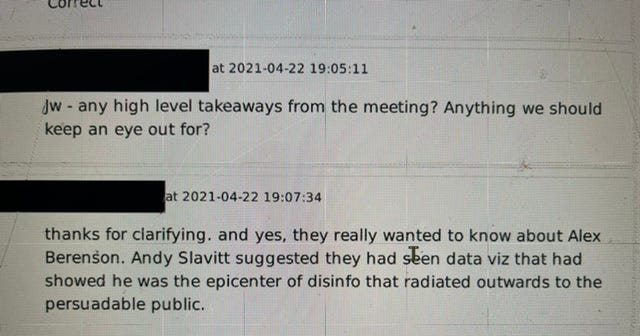

In August, Berenson published documents online that he received from Twitter as part of his lawsuit against the company. Twitter settled the lawsuit by restoring Berenson’s account, which it said the company should not have suspended in the first place. Among the documents Berenson released was this one:

The documents, from an internal Twitter Slack channel, reference a discussion between Twitter employees at the White House last April. At that time, Slavitt, who had been acting administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) under Barack Obama, was serving in the Biden administration’s covid task force. According to the Twitter Slack message, Slavitt pushed for action against Berenson, because the latter represented an “epicenter of disinfo[rmation] that radiated outwards to the persuadable public” regarding covid vaccines.

I will let others comment on the legal issues presented by this case, and the documents in question—whether Twitter violated its terms, and Berenson’s legal rights, in suspending Berenson, and whether the apparent pressure from administration officials represented an unconstitutional attempt by government employees to coerce a private actor (i.e., Twitter) to engage in state-sponsored censorship. But when it comes to Slavitt, he is in no position to talk, or criticize others, on promulgating “disinfo.”

Nonsense about Republican Legislation

Five years ago, Slavitt published a Twitter thread about Republicans’ “repeal-and-replace” Obamacare legislation that started thusly:

The entire thread sounded compelling—but it didn’t have any facts (or logic, for that matter). I outlined most of the policy details in a piece at the time, so won’t belabor them here. The quick-and-dirty version:

- States can eliminate their Medicaid programs any time they like, because the Constitution forbids the federal government from commandeering states and telling them what to do.

- Because of No. 1, there wasn’t any provision in the Republican bills allowing states to eliminate their Medicaid programs—nor was there (or is there) a provision in law prohibiting states from eliminating these programs.

- The waiver process Slavitt referred to in his thread relates to the Obamacare exchanges, and had no bearing on the Medicaid program. A document published while Slavitt headed CMS demonstrated this fact.

- A mutual colleague and New York Times reporter politely attempted to point this out to Slavitt, but he bulldozed ahead anyway with his (false) accusations.

At best, Slavitt had absolutely no clue how the Medicaid program works—meaning he never should have been appointed to run CMS in the Obama administration. At worst, he tried to derail legislation he didn’t like by publishing an incoherent set of falsehoods.

‘Epicenter of Disinfo’

It therefore seems more than a bit rich for a Twitter employee to quote Slavitt as saying Berenson served as an “epicenter of disinfo radiating outwards to the persuadable public” with regards to covid vaccines. Slavitt took a very similar role upon leaving the Obama White House in January 2017, working to marshal public opposition to Republican “repeal-and-replace” legislation that spring and summer.

In serving as one of the centers of the “resistance” to the Trump administration’s agenda, Slavitt didn’t just win more attention for himself. The “rabble-rouser” helped craft messaging points that others adopted in the media, in interactions with lawmakers, and so forth. In other words, when it comes to the above thread, he served as an “epicenter of disinfo that radiated outwards to the persuadable public”—exactly the same charge he leveled against Berenson.

Moreover, Slavitt’s actions hold particular relevance to Twitter’s policies. Those guidelines say that Twitter relies on “external, subject-matter experts” to police misinformation.

As a former head of the agency that runs Medicare and Medicaid, an outside observer might consider Slavitt such a subject-matter expert on the Medicaid program. It is therefore worth asking whether Slavitt’s posts received preferential treatment because of the prestige associated with his prior role, and notwithstanding their deviation from the facts.

I reached out to a Twitter representative, to ask for more details about how the company determines its subject-matter experts, whether those individuals or entities are publicly identified, and what happens if and when those experts make false or misleading statements themselves. The representative did not respond to my requests for comment.

Congress Should Investigate

Likewise, I reached out to Slavitt’s office, to ask if he wished to comment on his 2017 thread and more recent actions. His representative failed to acknowledge several requests for comment. However, in an interview with The Atlantic shortly after the documents’ release last month, Slavitt acknowledged meeting with representatives from Twitter during his time at the White House about disinformation, but claimed not to have raised Berenson specifically, with whom he said he only a vague familiarity.

I also reached out to Berenson, to see if he had any comment about Slavitt’s history of prior misleading tweets. He acknowledged my inquiry, but declined to comment, citing his announcement that he intends to take legal action against the Biden administration and Slavitt.

Regardless of the potential for additional litigation, Congress should investigate the details of this matter itself. If Republicans take over one or both chambers of Congress, they should subpoena not just Twitter executives, but Slavitt as well. Perhaps then this former Biden administration official can explain, to Congress and the world, how and why someone who engaged in misinformation himself saw fit to weaponize Big Tech against others.

This post was originally published at The Federalist.