AARP Puts Profits over Patients

A PDF copy of this report is available on the American Commitment website…

Why would an organization that brands itself as a seniors’ advocacy group support legislation that raids Medicare by more than a quarter-trillion dollars, diverting funds pledged to seniors’ health care into other government programs? Perhaps because its business partners will benefit financially from that raid.

Some Americans might think of AARP, formerly known as the American Association of Retired Persons, as a membership and advocacy organization. However, the reality has proven far different. AARP has grown into a marketing and sales firm with a public policy advocacy group on the side. And AARP’s prime source of tax-free revenue from that marketing operation comes from its relationship with UnitedHealth Group, the nation’s largest health insurer.

For decades, AARP has faced accusations of questionable business practices from numerous quarters: Federal officials, who suggested a business arrangement AARP proposed (but never implemented) could violate federal criminal statutes, the editorial board of the New York Times, and former AARP employees themselves.[1] The organization’s business practices embed “royalty fees” within the premiums of those who purchase Medicare supplemental policies, called Medigap insurance, effectively overcharging seniors to fund AARP’s operations. AARP’s revenue from these sales, and from UnitedHealth, which licenses AARP-branded Medigap and Medicare Advantage coverage, has grown every year for more than two decades straight. Since 2007, the organization has received an estimated $8.2 billion tax-free in revenue from UnitedHealth.

That money compromises AARP’s policy stances in many ways. For instance, in 2022, the organization endorsed Democratic legislation—the inaccurately named “Inflation Reduction Act”—that will over the next decade redirect more than $250 billion from the Medicare program into green-energy pork and other progressive projects.

Taking money from Medicare to pay for other programs will harm seniors, but sadly such tactics are par for the course for an organization that similarly endorsed Obamacare’s raid on Medicare in 2010. And in 2022, as with Obamacare in 2010, the “Inflation Reduction Act” also happens to benefit the bottom line of AARP’s insurance businesses, along with those of its partner, UnitedHealth.

An exploration of the record shows not just that AARP holds serious conflicts of interest, but that AARP’s financial conflicts have prompted the organization to abandon its principles on numerous occasions, pursuing financial gain for itself and its partners over the organization’s stated mission and policy objectives—and its members. Congress should follow up on these facts, and its own prior investigations, by further exploring the unsavory alliance between AARP and UnitedHealth Group.

A Doubly Harmful Bill

The AARP-endorsed “Inflation Reduction Act” contains two sets of policies that will harm seniors. First, by empowering the federal government to “negotiate” the prices of prescription drugs, the new law will reduce innovation and new drug discoveries. The Congressional Budget Office recently estimated that the “negotiation” provisions—in which federal bureaucrats will effectively dictate drug prices, and impose a tax of up to 95% on companies that do not comply—will result in at least 13 new drugs not becoming available over the coming decades.[2]

However, other experts believe that government price setting under the guise of “negotiation” will lead to a much greater reduction in the number of new therapies and cures. A November 2021 analysis of an earlier version of the legislation found that its drug pricing provisions would lead to a substantial decline in research and development activity, leading to 135 fewer new drugs being created.[3]

These therapies represent potential cures for cancer, Alzheimer’s, and other rare diseases not becoming available to seniors, because government bureaucrats interfered with the innovation process. In fact, the “negotiation” provisions could result in the loss of 331.5 million life-years—a much larger loss than that due to the COVID-19 pandemic—as the lack of new therapies means that patients die earlier than they would have done in a pro-innovation environment.[4]

As much harm as the drug “negotiation” provisions will cause, the savings generated from these price controls pose an added injury to seniors. According to the Congressional Budget Office, the “Inflation Reduction Act” reduces Medicare spending by a net of $254.8 billion—that is, more than a quarter-trillion dollars—over the coming decade.[5]

Where will those savings go? Not towards saving the Medicare program, and making it solvent for future generations. Instead, lawmakers redirected those Medicare dollars toward myriad other leftist causes. For instance, the Medicare savings will fund additional spending on Internal Revenue Service operations—including the hiring of nearly 87,000 IRS agents, according to one Treasury Department proposal—along with spending on various other green energy projects.[6]

Same Song, Second Verse

The structure of the “Inflation Reduction Act” resembles that of Obamacare. That legislation reduced Medicare spending by $716 billion over the law’s first decade—again, not to make Medicare solvent, but to fund new entitlements for younger Americans and other spending within the federal government.[7]

Unfortunately, leftist politicians have a history of using Medicare as a slush fund to finance their big-spending proposals elsewhere within government.[8] That trend began with Obamacare, and continued with the “Inflation Reduction Act.”

Just as unfortunate, AARP has a history of supporting legislative proposals that raid Medicare. In 2010, the organization endorsed Obamacare, despite loud opposition from many of its senior citizen members. Perhaps not coincidentally, Obamacare also happened to exempt Medigap supplemental insurance—a prime source of AARP’s revenue, as this paper will explain in detail below—from virtually all of the law’s new insurance regulations.[9]

Likewise, AARP had ulterior motives when it endorsed the “Inflation Reduction Act” this year. The law’s provisions arbitrarily lowering drug prices through price controls masquerading as “negotiation” will benefit both AARP and UnitedHealth Group, its insurer partner. Moreover, the approximately $64 billion cost of extending enhanced Obamacare subsidies for three years—paid for, as noted above, via the “raid” on Medicare—will benefit UnitedHealth’s business selling coverage on insurance Exchanges.[10]

That AARP attempts to ignore policy conflicts with its insurer partner, and likely its largest source of income, does not mean they do not exist. Instead, it should provide Congress with additional incentive to investigate and expose the financial conflicts that lie at the heart of this supposed seniors’ advocacy organization.

A Profitable “Non-Profit”

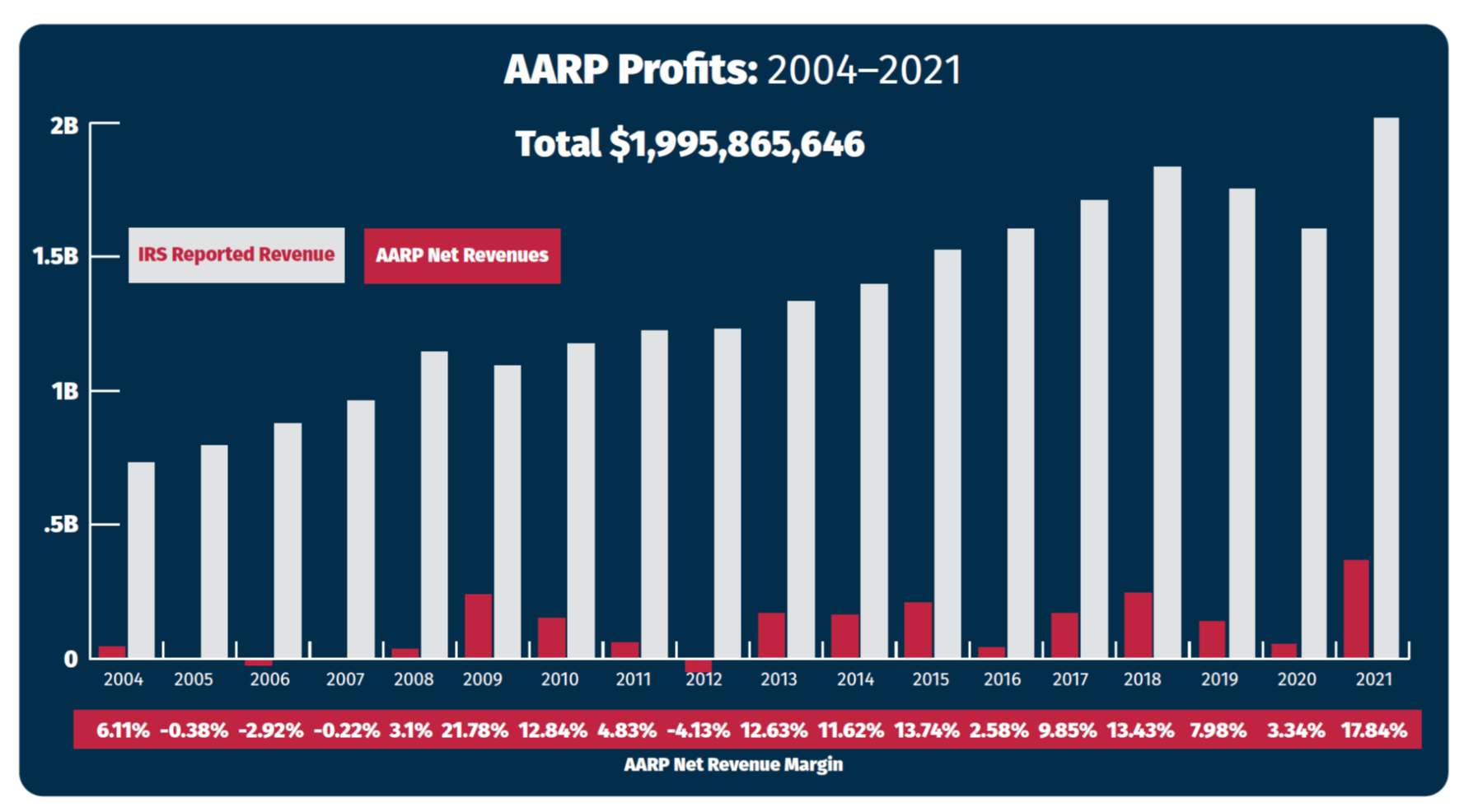

Despite the organization’s status as a non-profit entity organized under Section 501(c)(4) of the Internal Revenue Code, AARP has found its business very enriching indeed. According to its most recent Form 990 filed with the Internal Revenue Service, in 2021 the organization reported net income—that is, revenues in excess of expenses—of $356,898,359, on total revenues of just over $2 billion. [11]

This sizable net income does not represent an anomaly when it comes to AARP’s fortunes. After hiring Barry Rand as CEO in early 2009, AARP converted a string of modest annual results into a series of large financial gains. Under Rand and Jo Ann Jenkins, who succeeded him in 2014, AARP has achieved a total of nearly $1.6 billion in net profits since 2009, notching financial gains in all but one of those 11 years.[12] Moreover, its net revenue margin since 2009 has averaged nearly 10%, far more than the average profit margin of some industries.[13] For instance, of six health insurers listed in the 2021 Fortune 500, none had a profit margin exceeding 5.99%.[14]

A Marketing Behemoth

A Marketing Behemoth

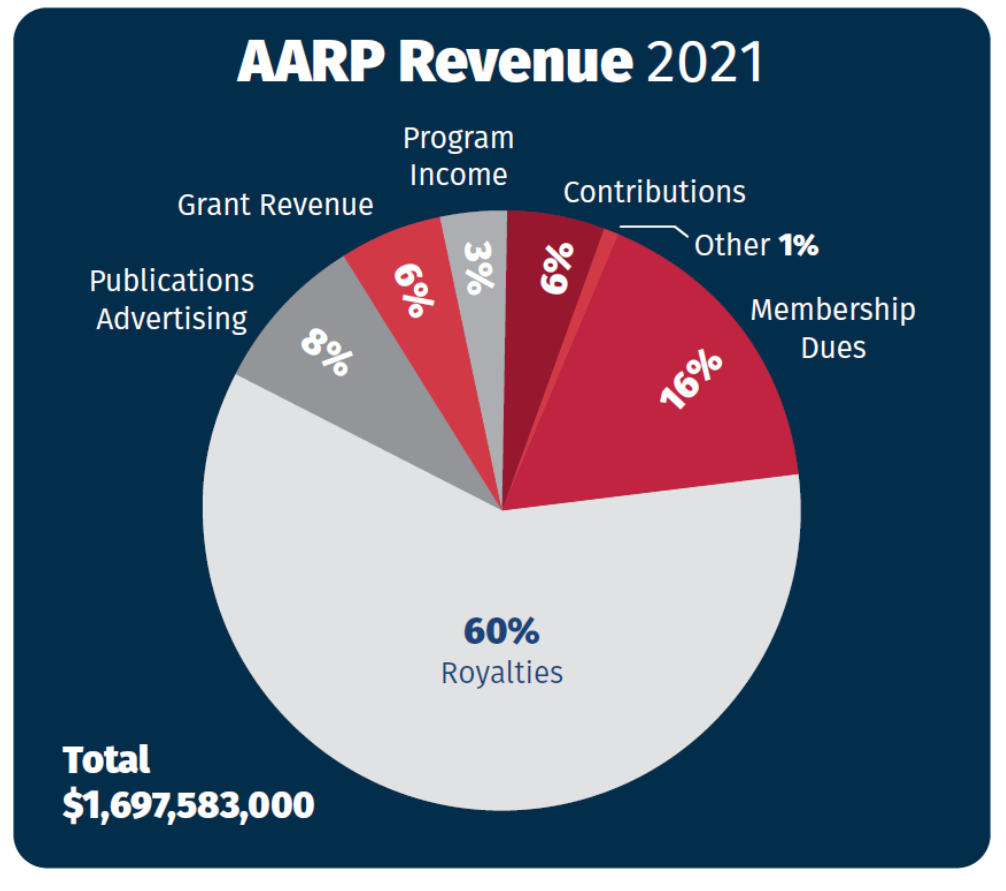

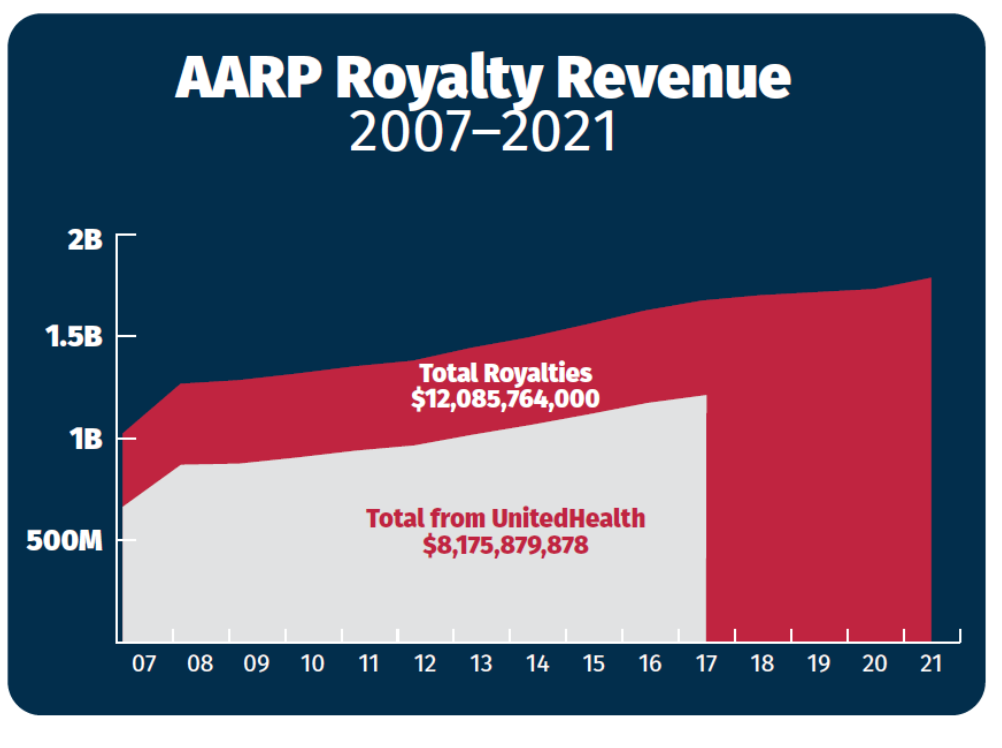

For all the revenue AARP receives from membership dues—just under $300 million in 2021, according to its most recent consolidated financial statements—the organization receives more than three times that amount selling AARP-branded goods and services to its members.[15] In fact, the organization’s “royalty fees”—which the organization claims constitute payments for the use of its logo, brand, and intellectual property—represent approximately 60% of AARP’s total annual revenues.[16] In 2021, AARP received nearly $1.1 billion in such revenue from what more appropriately constitutes the sale and marketing of products to members, more than double the revenues generated by membership dues, grant revenue, and contributions combined.[17]

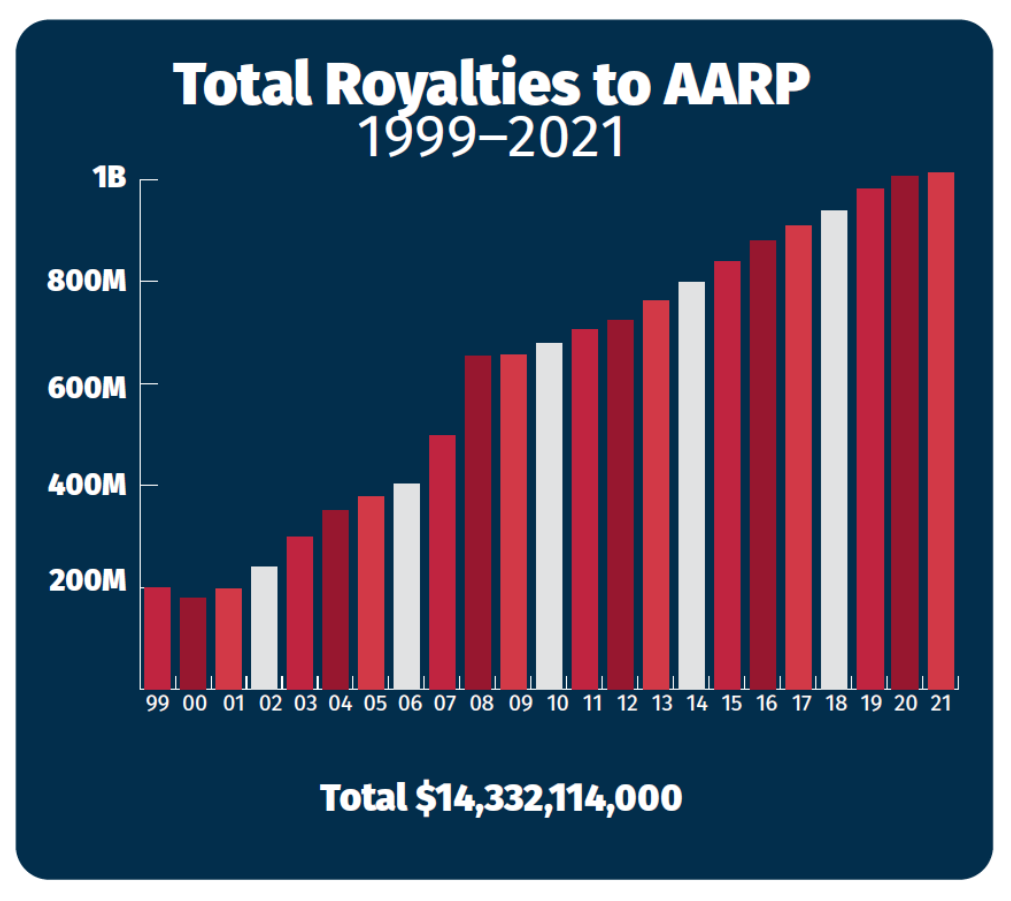

While other organizations’ revenues fluctuate from year to year, the revenue AARP has generated from selling products to its members has increased every single year for 21 years straight. Since 2000, the company’s business proceeds have increased nearly sixfold, from $178.3 million in 2000 to nearly $1.1 billion in 2021.[18] In total, over the past 23 years, AARP has made nearly $14.3 billion selling products to its members.[19]

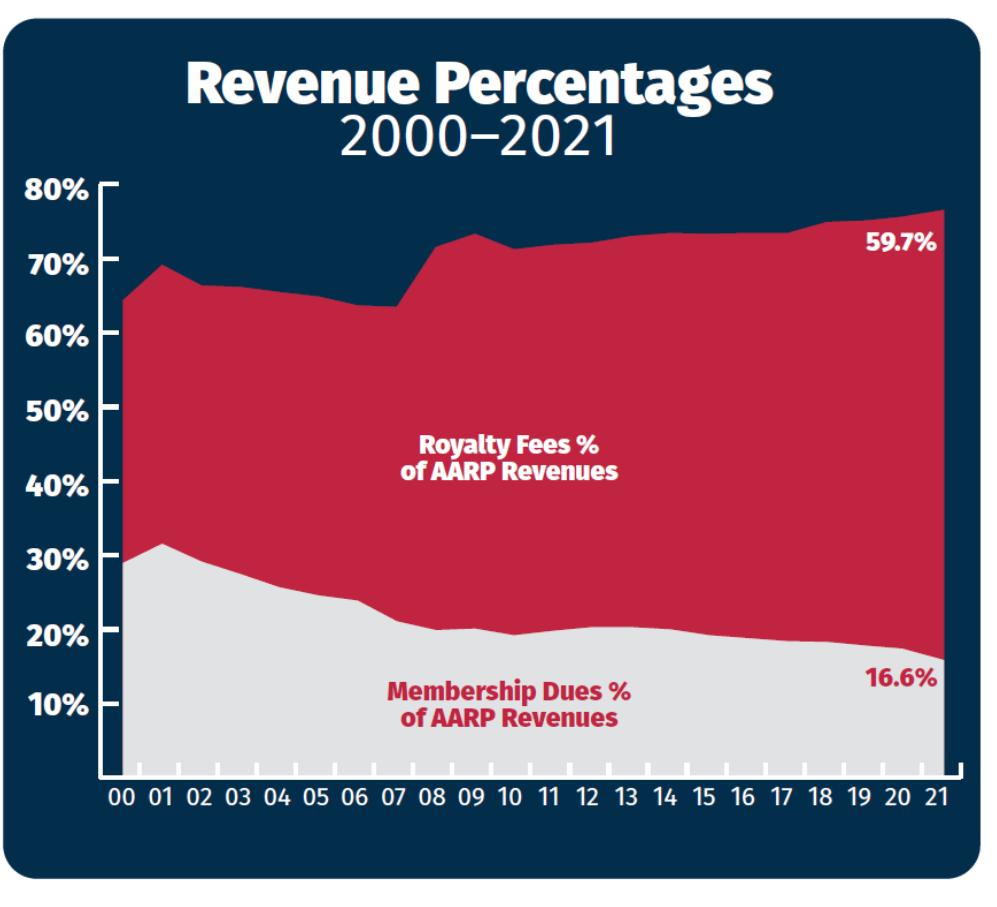

As AARP has expanded its marketing empire, fees from membership dues have grown at a much slower pace. While dues collections have risen over the past two decades, from $141.1 million in 1999 to nearly $300 million in 2021, since 2014 they have remained largely flat.[20] In some years, revenue from membership dues has declined year-on-year—a contrast to the organization’s marketing arm, where revenues have increased every single year since 2000.[21]

Last year typified the general trend. In 2021, even as membership dues slipped by more than $4.5 million, royalty revenues grew by over $61 million, to an all-time record.[22]

The result of the two trends—membership dues growing slowly, and royalty fees growing exponentially—has made AARP much more reliant on marketing income as a share of its overall revenues. Since 2000, membership dues have nearly halved as a percentage of AARP’s total operating revenues, from 28.9% to 16.6% in 2021.[23] Meanwhile, marketing income has grown from 35.6% of operating revenues to 59.7%, meaning AARP gets more than three times more of its budget from selling other products to members than it does from membership dues themselves.[24]

Health Insurance Business Dominates

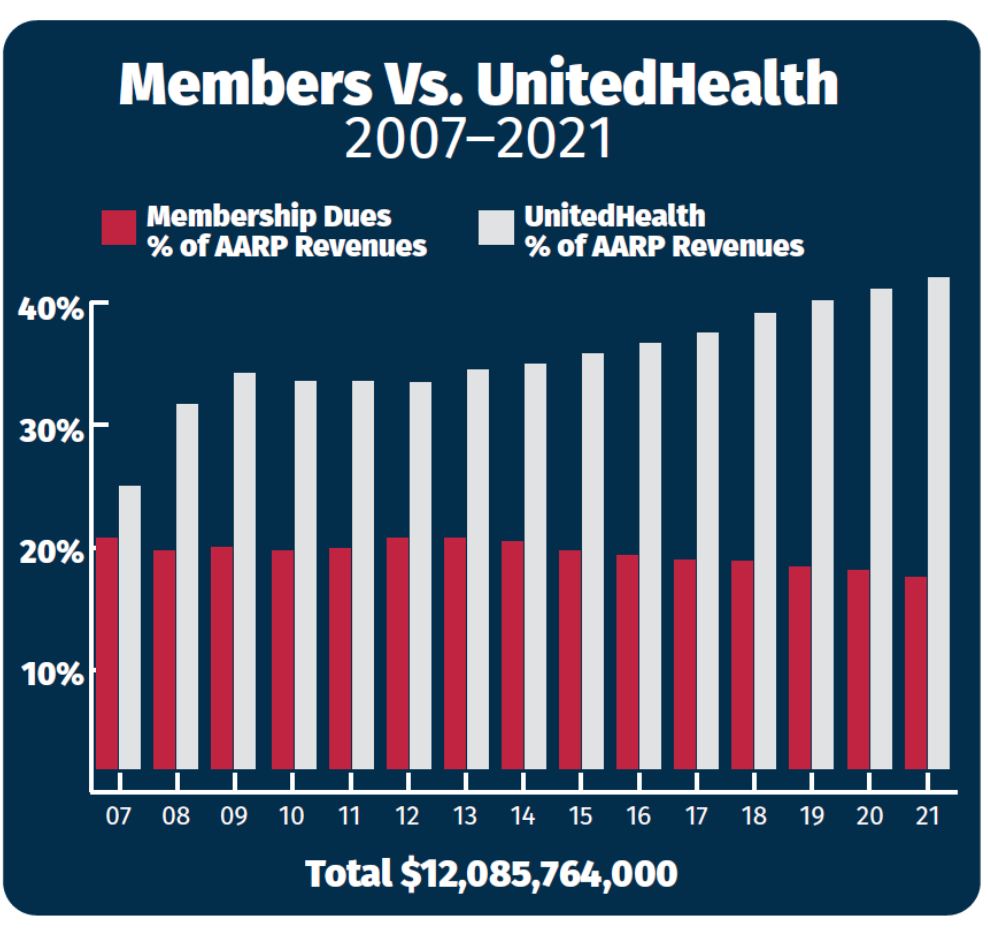

As AARP’s sales and marketing revenue has skyrocketed overall, the percentage of that revenue coming from UnitedHealth Group has also grown. In 2007, revenue from UnitedHealth represented 57% of AARP’s marketing income, or $283.7 million.[25] By 2017, both numbers had grown substantially: Income from UnitedHealth comprised 69% of AARP’s marketing revenue and had risen to a whopping $627.2 million—more than double the amount of just a decade previously.[26]

As income from UnitedHealth Group has grown over the past decade, so too has UnitedHealth’s share of AARP’s operating revenues. As of 2017, income from the sale of insurance products through UnitedHealth exceeded income from membership dues by almost twofold.[27] While member dues comprised only 18.3% of the organization’s total revenue in 2017, UnitedHealth revenue constituted 38.2% of AARP’s operating income.[28]

AARP’s relationship with UnitedHealth Group, discussed in further detail below, has drawn public scrutiny from Congress and other policymakers. From 2008 through 2017, AARP’s consolidated financial statements disclosed the percentage of marketing revenue coming from UnitedHealth. One could therefore easily calculate the exact amount of revenue AARP received from UnitedHealth, by multiplying total marketing revenues by the percentage of those revenues coming from UnitedHealth Group. In total, from 2007 through 2017, AARP received more than $5.3 billion tax free from UnitedHealth Group.[29]

AARP’s relationship with UnitedHealth Group, discussed in further detail below, has drawn public scrutiny from Congress and other policymakers. From 2008 through 2017, AARP’s consolidated financial statements disclosed the percentage of marketing revenue coming from UnitedHealth. One could therefore easily calculate the exact amount of revenue AARP received from UnitedHealth, by multiplying total marketing revenues by the percentage of those revenues coming from UnitedHealth Group. In total, from 2007 through 2017, AARP received more than $5.3 billion tax free from UnitedHealth Group.[29]

However, beginning in 2018, AARP’s consolidated financial statements failed to disclose the exact percentage of its marketing revenue coming from UnitedHealth Group.[30] Therefore, one can no longer calculate the precise amount of income AARP receives from UnitedHealth. We do know that AARP’s marketing revenue has grown every single year since 2000, and that the percentage of overall marketing revenue coming from UnitedHealth stayed the same or increased every year from 2007 to 2017.[31]

However, beginning in 2018, AARP’s consolidated financial statements failed to disclose the exact percentage of its marketing revenue coming from UnitedHealth Group.[30] Therefore, one can no longer calculate the precise amount of income AARP receives from UnitedHealth. We do know that AARP’s marketing revenue has grown every single year since 2000, and that the percentage of overall marketing revenue coming from UnitedHealth stayed the same or increased every year from 2007 to 2017.[31]

Because AARP decided to stop disclosing the percentage of “royalty” revenue received from UnitedHealth Group to its members or the public—quite possibly due to increased public scrutiny over its relationship with UnitedHealth—we can no longer calculate the amount precisely.[32] However, AARP added a section to its financial statements regarding revenue recognition, which includes an additional discussion of royalties.[33] Because information in the 2018 statements includes data for the prior year period, and because AARP did provide information on its revenue from UnitedHealth in its 2017 statements, we can create an approximation of its UnitedHealth revenue for 2018 and subsequent years.

In its 2018 financial statements, AARP claimed that $649.2 million of royalty revenue in 2017 came from “health products and services.”[34] In its 2017 statements, AARP noted that a total of $627.2 million in royalty revenue—or 96.6% of the “health products and services” royalties—came from UnitedHealth.[35] If UnitedHealth accounted for a similar 96.6% share of the $680.3 million in “health products and services” revenue in subsequent years, that would mean AARP received a total of about $657.2 million in revenue from UnitedHealth in 2018.[36] Likewise, if UnitedHealth accounted for a 96.6% share of the $814 million in “health products and services” revenue AARP reported in 2021, that would mean the organization received $786 million from UnitedHealth.[37] Revenue in this range would mean AARP received an estimated $8.2 billion in “royalty” income from UnitedHealth since 2007.[38]

While these numbers serve as mere approximations, they do so only because AARP decided to stop disclosing to the public exactly how much money it received from UnitedHealth Group. AARP’s actions reflect a lack of transparency on its part, and potentially a desire to mask its financial dependence on UnitedHealth.

In 2019, AARP issued a position statement calling on state governments to “enact laws that promote transparency” and “require pharmaceutical companies to justify high launch prices and price hikes.”[39] Yet as Congress prepared to consider major Medicare legislation this summer, AARP acted in a non-transparent manner regarding the windfall “royalty” revenue it takes in from selling Medicare insurance policies, failing to post publicly until September an annual financial statement that its accountants had finalized in March.[40] This delay denied AARP members, the general public, and Members of Congress interested in these issues a real-time look into the organization’s financial activities, and potential conflicts of interest arising from them.

Making Money on Seniors’ Money

AARP not only makes money from UnitedHealth Group—and its members—directly, it also does so indirectly as well. The organization has established a grantor trust, through which it funnels payments for insurance policies issued by UnitedHealth and other insurers, including MetLife, Genworth, and Aetna. As its financial statements explain:

The [AARP Insurance] Plan, a grantor trust, holds group policies, and maintains depository accounts to initially collect insurance premiums received from participating members. In accordance with the agreements referred to above, collections are remitted to third-party insurance carriers within contractually specified periods of time, net of the contractual royalty payments that are due to AARP, Inc., which are reported as royalties in the accompanying consolidated statements of activities.[41]

In plain English, this language means that members pay premiums—including the “royalty fee” UnitedHealth pays to AARP—via the trust, and the AARP trust then pays the premium to UnitedHealth, after taking out its own “royalty fees.”

But in the process, AARP invests the funds from the day they receive the payments from seniors until the “contractually specified” time during which they transfer the payments to UnitedHealth Group and other insurers. Investing seniors’ premium payments for a short period might seem insignificant. However, given the massive sums involved—the grantor trust processed a total of $11.8 billion in payments from AARP members in 2021—the investment gains quickly add up.[42]

Over the past two decades, AARP has made nearly a billion dollars—$807.2 million, to be exact—investing seniors’ premium payments via its grantor trust.[43] In only three years—during the market crash in 2008, in 2015, and in 2018—did AARP lose money in its investments made via the grantor trust.[44] On average, however, the organization made $35.1 million per year via these investments—much, but not all, of which came from premium payments made by members for UnitedHealth Group insurance.[45]

Extravagant Compensation & Benefits

In 2021, AARP paid its CEO, Jo Ann Jenkins, a total of $2,708,809 in salary, benefits, and other compensation.[46] The payout continued a long-standing tradition of the organization spending large sums on executive compensation. In 2006, AARP paid its then-CEO, Bill Novelli, over $2 million in compensation—this in a year when AARP suffered a nearly $26 million shortfall.[47] And when Novelli’s successor, Barry Rand, retired on September 1, 2014, he received nearly $1.7 million in compensation—after working for only eight months out of the year.[48]

But the high compensation levels do not stop with AARP’s CEO. Of a total of 15 AARP other officers, key employees, and other highly compensated staff listed on the organization’s 2021 Form 990 filed with the Internal Revenue Service, all but one received more than $500,000 in total compensation.[49] These figures only include the salaries and compensation for key executives for which the IRS requires disclosure. By definition, it does not include other AARP executives, or executives of the AARP Foundation, a separate legal entity with its own salaried officers and staff.

According to its IRS filing, in 2021 nearly 65% (1,307) of AARP’s total employees (2,023) received reportable compensation from the organization in excess of $100,000.[50] Dividing the organization’s total spending on employee compensation in 2021 ($382,613,652) by its number of employees (2,023) reveals that AARP employees received an average of $189,131.81 in salaries, benefits and other compensation—this at a time when the COVID pandemic continued to wreak havoc on the economy, including on the retirement balances of many seniors.[51]

By comparison, in 2021 the average senior citizen received $1,543 in monthly Social Security benefits.[52] That $18,516 total annual benefit represents less than one-tenth the total compensation provided to the average AARP employee. To put it another way, in 2021 AARP paid over $85 million more in compensation to its employees than the organization itself received in dues from its members—and $340 million more than AARP spent giving grants to other organizations.[53]

Furthermore, AARP officials have admitted that the organization’s overall revenue totals—including “royalty fees” obtained by selling seniors AARP-branded products—impact the compensation decisions of its senior executives. As one anonymous staffer told the Washington Post, “Revenues are very important. You have to make your numbers.”[54] In other words, if AARP does not receive enough “royalty fees” from selling products to its members, its CEO and other senior executives could lose bonuses or other financial compensation.

Medigap: The AARP Cash Cow

As noted above, AARP has received a stunning amount of revenue—an estimated $8.2 billion—from UnitedHealth Group since 2007. However, the organization does not delineate how much of said revenue comes from each of the three types of plans UnitedHealth sells: Medicare Advantage plans, Medicare Part D prescription drug coverage, and Medigap supplemental coverage. A 2011 report by the House Ways and Means Committee found that AARP brands held dominant market shares in all three categories.[55]

However, among the three forms of coverage, AARP receives a flat annual “royalty fee” from UnitedHealth covering the sale of its AARP-branded Part D and Medicare Advantage plans, regardless of the plans’ enrollment. Conversely, for Medigap coverage, AARP receives a “royalty fee” from UnitedHealth equal to 4.95% of premium revenues paid.[56]

This percentage-based “royalty fee” gives AARP a strong financial incentive to aggressively market, sell, and renew as many Medigap policies as possible—and the most expensive policies at that—because AARP receives nearly five cents for every additional premium dollar its members pay to UnitedHealth. Perhaps as a result, some of AARP’s own members have considered these revenues not so much “royalty fees” as “kickbacks.”[57]

That 4.95% “royalty fee” represents a sizable share of premium dollars paid. To put the figure into perspective, it exceeds the current profit margins of five publicly held health insurers (Anthem, Centene, Humana, Molina, and Triple-S Management), and approaches the profit margin of the other (UnitedHealth Group).[58]

More to the point, AARP’s “royalty” margins come even though the organization bears no financial risk. The organization often notes that it is “not an insurance company”—a very true statement.[59] Insurers like UnitedHealth, Anthem, and Humana must take on financial risk, and can lose money in down markets or under turbulent circumstances. For instance, insurers lost an estimated $2.7 billion selling individual insurance policies in 2014, the first year of Obamacare’s Exchanges, and even more in the year following.[60] By contrast, however, AARP bears no risk, such that it cannot lose—all it has to do is sign up individuals and watch the cash roll in by the billions.

To give some sense of the questionable propriety of AARP’s current arrangements with UnitedHealth, in 1997 the group abruptly abandoned its plans for a percentage-based “royalty fee” for selling Medicare managed care plans (the precursor to Medicare Advantage).[61] At the time, government officials believed the arrangement potentially violated the Anti-Kickback Statute, which imposes criminal penalties for anyone who gives a “thing of value” in exchange for referrals of individuals to federal health programs.[62] The then-head of the agency that runs Medicare, Bruce Vladeck, also reportedly thought the arrangement could cause AARP to “lose its credibility as an advocate for its members if it endorses HMOs [Health Maintenance Organizations] and receives a financial reward.”[63]

Even though potential concerns that the arrangement violated a criminal statute led AARP to abandon its plans for percentage-based “royalties” to sell Medicare Advantage coverage, the organization has retained that approach when selling Medigap coverage—and has profited handsomely from it. Publicly available information suggests that most of AARP’s revenue from UnitedHealth comes via the sale of Medigap plans.

According to UnitedHealth’s annual filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission, in 2021 the insurer enrolled 4,395,000 individuals in AARP-branded Medicare supplemental (i.e., Medigap) plans.[64] Data from an online broker indicate that in 2021, seniors purchased Medigap policies with an average premium of $178 per month, or $2,136 per year.[65] Based on an average Medigap premium of $2,136 annually, UnitedHealth received about $9.4 billion in total Medigap premiums from its members in 2021. AARP’s 4.95% share of that sum would total roughly $465 million.

Again, these numbers represent approximations, because AARP does not disclose the amount of money it receives from selling various health insurance policies—and since 2018, does not disclose the exact sum it receives from UnitedHealth at all. But it strongly suggests that the majority of the approximately $800 million it receives from UnitedHealth in “royalty fees” comes from the sale of Medigap plans. It also suggests that AARP made far more money selling Medigap insurance to its members than the $300 million it received in membership dues.[66]

A Compromised Organization

The sordid history of AARP’s dealings in Washington—the legally questionable way it has conducted its business to obtain billions of dollars in profits, and its decades-long history of supporting legislation that raids the Medicare program to fund other leftist priorities—demonstrate how its revenue sources have compromised the integrity of its policy positions.

As one observer noted several years ago: “Either you’re a voice for the elderly or you’re an insurance company—choose one.”[67] Sadly, AARP has largely chosen the latter course of action, becoming reliant on UnitedHealth for a significant share of its revenue, even as it tries to portray itself as the former.

Congress has investigated AARP and its financial dealings on more than one occasion. It should do so again, and determine whether any legislative and/or regulatory actions—requiring AARP to disclose its financial conflicts to seniors when they apply for Medigap coverage, for instance—can protect AARP’s members from the organization’s unholy alliance with UnitedHealth Group.

[1] Milt Freudenheim, “AARP Dropping Plans for Royalties in a Health Program,” New York Times April 19, 1997, https://www.nytimes.com/1997/04/19/business/aarp-dropping-plans-for-royalties-in-a-health-program.html; “Can You Trust the AARP?” New York Times May 20, 1996, https://www.nytimes.com/1996/05/20/opinion/can-you-trust-the-aarp.html; Jerry Markon, “AARP Lobbies Against Medicare Changes That Could Hurt Its Bottom Line,” Washington Post December 4, 2012, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/aarp-lobbies-against-medicare-changes-that-could-hurt-its-bottom-line/2012/12/03/aa3e509e-3a8c-11e2-b01f-5f55b193f58f_print.html.

[2] Congressional Budget Office, cost estimate for Inflation Reduction Act as enacted, September 7, 2022, https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2022-09/PL117-169_9-7-22.pdf, p. 15.

[3] Tomas J. Philipson and Troy Durie, “The Impact of H.R. 5376 on Biopharmaceutical Innovation and Patient Health,” University of Chicago Issue Brief, November 29, 2021, https://cpb-us-w2.wpmucdn.com/voices.uchicago.edu/dist/d/3128/files/2021/08/Issue-Brief-Drug-Pricing-in-HR-5376-11.30.pdf.

[4] Ibid.

[5] CBO, cost estimate of Inflation Reduction Act. Figure reflects total Medicare savings of $299.3 billion, less a total of $44.5 billion in new Medicare spending provisions included in the legislation.

[6] Chris Jacobs, “‘Build Back Better’ Bill Would Fund 86,000 Additional IRS Agents to Sic on American Taxpayers,” The Federalist July 29, 2022, https://thefederalist.com/2022/07/29/build-back-better-bill-would-fund-86000-additional-irs-agents-to-sic-on-american-taxpayers/; U.S. Treasury Department, “The American Families Plan Tax Compliance Agenda,” May 2021, https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/The-American-Families-Plan-Tax-Compliance-Agenda.pdf, Table 3: IRS Proposal and Revenue Raised, 2022-2031, p. 16.

[7] Congressional Budget Office, cost estimate of H.R. 6079, Repeal of Obamacare Act, July 24, 2012, https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/43471-hr6079_0.pdf, p. 13.

[8] Chris Jacobs, “Democrats Use Medicare as a Piggy Bank,” Wall Street Journal March 25, 2021, https://www.wsj.com/articles/democrats-use-medicare-as-a-piggy-bank-11616624520.

[9] Karl Rove, “Obamacare Rewards Friends, Punishes Enemies,” Wall Street Journal January 6, 2011, https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052748704405704576063892468779556.

[10] CBO, cost estimate of Inflation Reduction Act.

[11] AARP Inc., 2021 Form 990, https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/about_aarp/annual_reports/2022/2021-aarp-form-990-public-disclosure2.pdf, p. 1.

[12] AARP Inc., Forms 990, 2009 through 2021. While only the 2019, 2020, and 2021 statements are visible on the organization’s website, https://www.aarp.org/about-aarp/company/annual-reports/, all copies of the AARP Forms 990 are available through a ProPublica database, https://projects.propublica.org/nonprofits/organizations/951985500.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Fortune 500, 2021, https://fortune.com/fortune500/2021/search/?f500_industry=Health%20Care%3A%20Insurance%20and%20Managed%20Care. Health insurers include UnitedHealth Group, Anthem, Centene, Humana, Molina Healthcare, and Triple-S Management. The other Fortune 500 company listed under “Insurance and Managed Care,” Magellan Health, focuses on managing behavioral health issues, as opposed to selling health insurance products to individuals and/or employers.

[15] AARP Inc., 2021 Consolidated Financial Statements, March 16, 2022, https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/about_aarp/annual_reports/2022/aarp-2021-financial-statement.pdf, p. 6.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] AARP Inc., Consolidated Financial Statements, 2000 through 2021. While only the 2019, 2020, and 2021 statements are visible on the organization’s website, https://www.aarp.org/about-aarp/company/annual-reports/, Internet searches for “AARP Consolidated Financial Statements” and the year in question reveal that prior years’ statements remain online (albeit not linked from the AARP homepage). Links to specific years’ statements are provided in citations below.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid.

[22] 2021 Consolidated Financial Statements, pp. 6-7.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

[25] AARP Inc., 2008 Consolidated Financial Statements, March 30, 2009, https://assets.aarp.org/www.aarp.org_/TopicAreas/annual_reports/assets/AARPConsolidatedFinancialStatements.pdf, pp. 4, 9. The 2008 financial statements represent the first instance in which AARP disclosed the percentage of total royalties coming from UnitedHealth Group. However, the 2008 statements also included data for the prior year period, making calculations for 2007 possible.

[26] AARP Inc., 2017 Consolidated Financial Statements, March 16, 2018, https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/about_aarp/about_us/2018/aarp-2017-audited-financial-statement.pdf, pp. 4, 11.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid.

[29] 2008 through 2017 Consolidated Financial Statements.

[30] 2018 Consolidated Financial Statements. The relevant language previously appeared in the royalties section of the statements’ Summary of Significant Accounting Practices. The 2018 statements’ Summary of Significant Accounting Practices eliminates the discussion of royalties entirely. Compare pp. 8-13 of the 2017 Statements with pp. 8-13 of the 2018 Statements.

[31] 2008 through 2017 Consolidated Financial Statements.

[32] Chris Jacobs, “How AARP Made Billions Denying Care to People with Pre-Existing Conditions,” The Federalist October 11, 2018, https://thefederalist.com/2018/10/11/aarp-made-billions-denying-care-people-pre-existing-conditions/.

[33] 2018 Consolidated Financial Statements, pp. 14-15.

[34] Ibid.

[35] 2017 Consolidated Financial Statements, pp. 4, 11.

[36] 2018 Consolidated Financial Statements, p. 14.

[37] 2021 Consolidated Financial Statements, p. 15.

[38] 2008 through 2019 Consolidated Financial Statements.

[39] AARP, Inc., “Support Drug Price Transparency,” https://www.aarp.org/politics-society/advocacy/info-2019/prescription-drugs-price-transparency.html.

[40] 2021 Consolidated Financial Statements, p. 4.

[41] 2021 Consolidated Financial Statements, p. 19.

[42] Ibid, p. 20.

[43] 2000 through 2021 Consolidated Financial Statements.

[44] 2008 Consolidated Financial Statements, p. 15; AARP Inc., 2015 Consolidated Financial Statements, March 17, 2016, https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/about_aarp/annual_reports/2016/2015-financial-statements-AARP.pdf, p. 14; 2018 Consolidated Financial Statements, p. 19.

[45] 2000 through 2021 Consolidated Financial Statements. While AARP has previously disclosed that most of its royalty fees come from UnitedHealth Group, AARP has never disclosed the precise percentage of grantor trust investment income attributable to policies sold by UnitedHealth.

[46] 2021 Form 990, p. 7.

[47] AARP Inc., 2006 Form 990, https://projects.propublica.org/nonprofits/display_990/951985500/2008_02_EO%2F95-1985500_990O_200612, pp. 1, 14.

[48] AARP Inc., 2014 Form 990, https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/about_aarp/annual_reports/2015-08/2014-IRS-Form-990-AARP.pdf, p. 10.

[49] 2021 Form 990, pp. 7-8.

[50] Ibid., pp. 1, 8.

[51] Ibid., pp. 1, 8.

[52] Social Security Administration, “Fact Sheet: 2021 Social Security Changes,” https://www.ssa.gov/news/press/factsheets/colafacts2021.pdf.

[53] 2021 Form 990, p. 1; 2021 Consolidated Financial Statements, p. 7.

[54] Markon, “AARP Lobbies Against Changes.”

[55] House Ways and Means Committee, “Behind the Veil: The AARP America Doesn’t Know,” March 30, 2011, https://gop-waysandmeans.house.gov/UploadedFiles/AARP_REPORT_FINAL_PDF_3_29_11.pdf, Table 2, p. 9.

[56] Ibid., pp. 11-12.

[57] Gary Cohn and Darrell Preston, “AARP’s Stealth Fees Often Sting Seniors with Costlier Insurance,” Bloomberg December 4, 2008, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2008-12-04/aarp-s-stealth-fees-often-sting-seniors-with-costlier-insurance.

[58] 2021 Fortune 500.

[59] Lee Hammond, AARP President, Letter to the Editor, Wall Street Journal January 11, 2011, https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052748704415104576065993584399626.

[60] McKinsey, “Exchanges Three Years In: Market Variations and Factors Affecting Performance,” May 2016, https://healthcare.mckinsey.com/exchanges-three-years-market-variations-and-factors-affecting-performance.

[61] Freudenheim, “AARP Dropping Plans.”

[62] Ibid.; Section 1128B of the Social Security Act, 42 U.S.C. 1320a-7b.

[63] Freudenheim, “AARP Dropping Plans.”

[64] UnitedHealth Group, Inc, 2021 Form 10-K, February 15, 2022, https://www.unitedhealthgroup.com/content/dam/UHG/PDF/investors/2021/UNH-Q4-2021-Form-10-K.pdf, p. 36.

[65] eHealthInsurance, “Medicare Index Report for 2022 Coverage,” April 2022, https://news.ehealthinsurance.com/_ir/68/20223/Medicare_AEP_Index_Report_2022_Coverage.pdf, p. 4. The author previously served as a paid lobbyist for eHealthInsurance.

[66] 2018 Consolidated Financial Statements, p. 4.

[67] Dan Eggen, “AARP: Reform Advocate and Insurance Salesman,” Washington Post October 27, 2009, https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/10/26/AR2009102603392_pf.html.