Budget Analysis Reveals Problems Behind Student “Loans”

The old aphorism calls a picture worth 1,000 words. But in at least one case, a series of pictures can be worth more than $1 trillion.

A recent report from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) provides helpful charts showing the many problems associated with the current federally subsidized loan program. As with many crises caused by government, the problem with student debt has many causes, and Democrats’ proposed “solution” — making all taxpayers responsible via massive “loan forgiveness” — would only make the problem worse.

Students Not Repaying ‘Loans‘

The CBO analysis examined federal student loans that began repayment from July 2009 to June 2013, tracking those loans through 2019. The period analyzed came after the worst of the Great Recession and before the Covid pandemic scrambled the economy and led to a massive student loan amnesty in 2020.

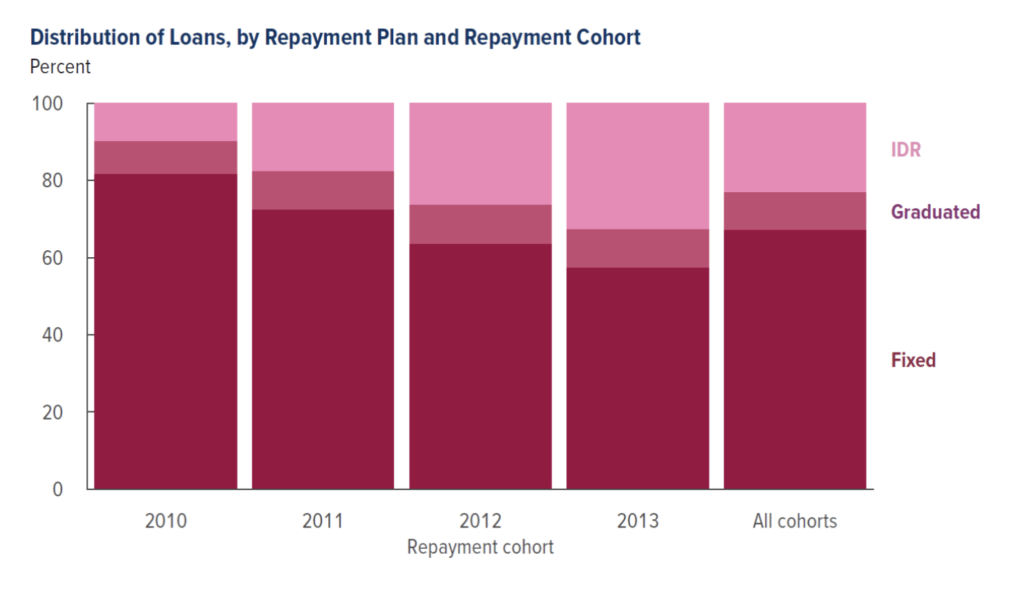

Over the four years examined, the percentage of borrowers who chose income-driven repayment (IDR) more than tripled, from 10 percent in the first year to 33 percent in the fourth year:

As CBO explained, while fixed payments remain constant throughout the entire repayment period, the IDR process “allow[s] repayment over a longer period — typically 20 or 25 years instead of the usual 10 — after which any remaining balance is forgiven,” and can require “payments” of as little as $0, which “still count towards the total number of payments required for forgiveness.”

Unsurprisingly, the number of debtors choosing this option has grown “as plans with smaller expected payments and earlier loan forgiveness have been introduced and become more widely known.” The movement toward IDR and zero-dollar “payments” meant that debtors made substantive payments — defined as a monthly amount of at least $10 — in only 38 percent of the months in which an average loan was in repayment status.

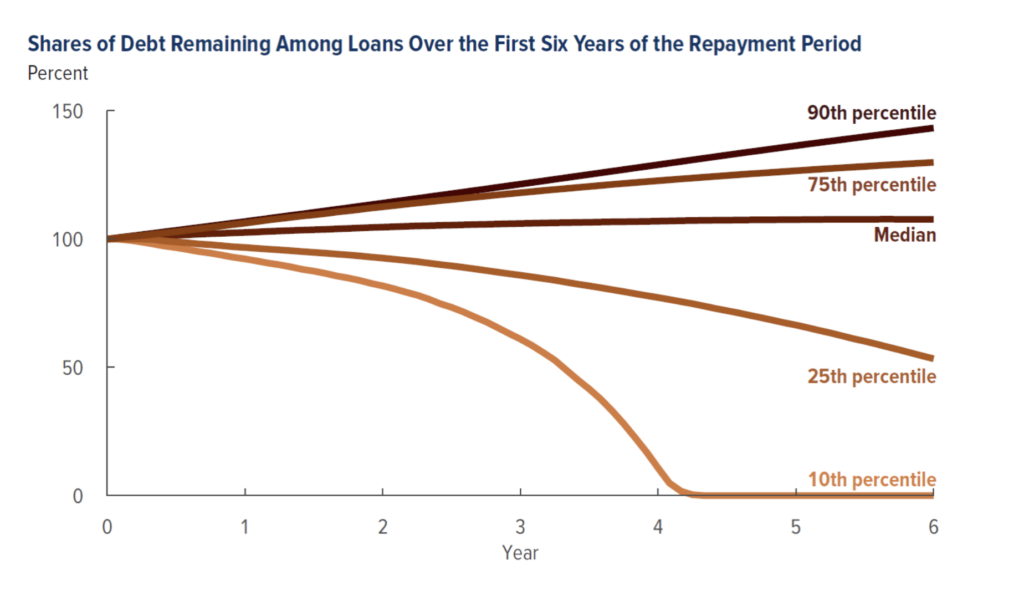

With borrowers making substantive repayments only about one-third of the time, it should surprise no one that after six years, the amount owed by the median (i.e., 50th percentile) borrower rose rather than fell:

Some borrowers paid off their loans in full — in fact, nearly 10 percent had done so by the end of four years, and another 15 percent had shrunk their balance roughly in half by the end of the six years studied.

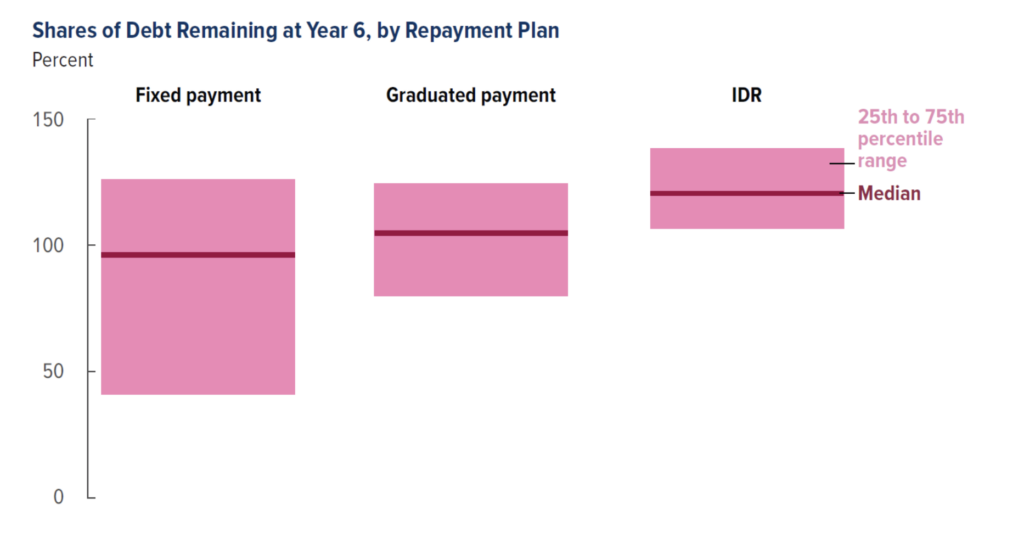

But on the flip side, a majority of borrowers saw their loan balances rise after six years, because their “payments” (such as they were) did not exceed the amount of interest that had accumulated on the loan. It should surprise no one that those in income-driven repayment made the fewest substantive payments and were much more likely to see their balance grow. In fact, more than three-quarters of participants in IDR saw their loan balance grow over the six-year period, whereas a slim majority of those using fixed repayments saw their balance shrink:

The data points show how much the IDR process has turned “loan repayment” into a joke. Borrowers are eagerly signing up for a plan that frequently sees them repaying little to nothing, which only makes their debt grow larger. As more borrowers play the IDR game, Democrats are citing this “crisis” created by wholesale nonpayment to argue for loan forgiveness.

The ‘College Con’

However, other elements of the CBO report show additional facets to the student loan story. For instance, nearly three-quarters (72 percent) of the loans were made to recipients of federal Pell grants, who by definition have lower incomes. One-third of loans (33 percent) went to students (both Pell recipients and non-Pell recipients) who financed only one or two years of undergraduate education. Many of these students likely did not complete even an associate’s degree and therefore have little to no additional earning power as a result of the time they spent in college.

Unsurprisingly, therefore, individuals who financed only one or two years of college were less likely than those who completed an undergraduate or graduate degree to make substantive repayments. People who financed only one year of undergraduate education were more than three times more likely to default on their loans (41 percent) than “those who financed upper-level undergraduate study” (12 percent). Borrowers who financed only one or two years of undergraduate education were more likely to owe more on their loans after six years than when they had started.

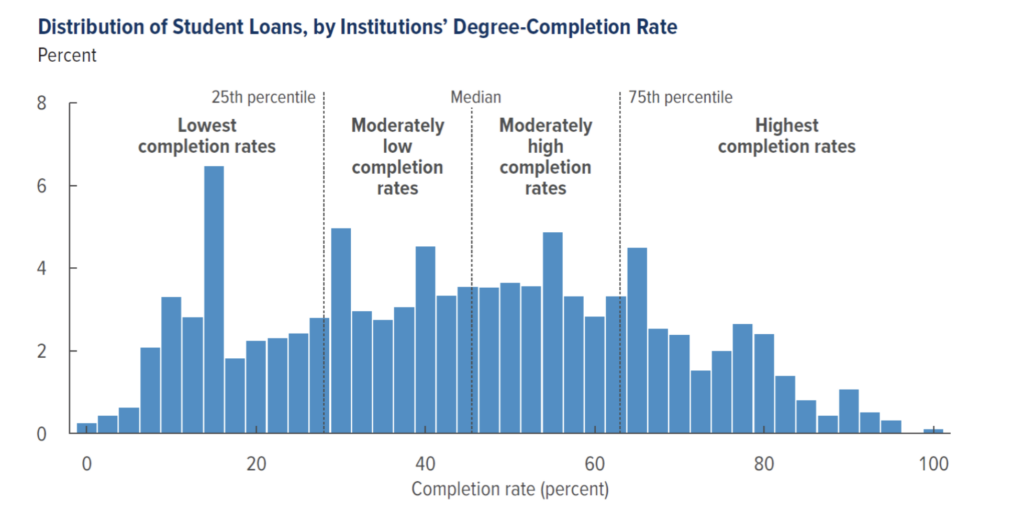

The most telling chart from the entire CBO report dealt with degree-completion rates. Half of the federal student loans issued went to students attending schools where fewer than 46 percent of students graduated:

Think about that for a moment: More than half of all federal student loans go to students attending institutions where more than half of students don’t graduate. Only one-quarter of students receiving loans attend institutions where 63 percent of students graduate — and even a 63 percent “success” rate constitutes an “F” in many grading systems. Unsurprisingly, the loans from institutions where more students graduate are likelier to get repaid.

Rethinking College

All these data points suggest that, yes, we do have a problem with some students gaming the system and using income-driven repayment to avoid paying back their loans. But we have an even bigger problem with the institutions that purport to “educate” these students yet leave more than half without degrees.

The reasons for this dynamic are many. In some cases, students may not belong in college — or at least not directly after high school. They could benefit from vocational and technical education, or more experience and maturity, to make a more informed choice about a potential career path before embarking on a costly education.

In far too many cases, colleges and universities aren’t taking responsibility for their charges. The CBO data regarding college completion makes the student loan program look like a money grab for higher education institutions, who seem more interested in attracting students’ federal loan dollars than giving them value for money in the form of a degree they can use to increase their earning power — and repay their loans. Their efforts to improve student retention and graduation haven’t shown results.

The tragedy is compounded by the fact that the overwhelming majority of loans get issued to Pell grant recipients. These students got sold on a college education as the way to achieve the American Dream yet ended up bogged down with debt attending an institution that in most cases didn’t do much to help them graduate. And Democrats’ plan to forgive their loans wouldn’t solve the fact that many of these individuals never received a degree or marketable skills that can help them in the workplace.

Particularly given the ideology that dominates most universities, conservatives should have zero qualms about imposing strict requirements for institutions whose students 1) don’t graduate and 2) don’t repay their loans. It’s long past time for taxpayers to stop subsidizing woke indoctrination that doesn’t make students smarter — or richer.

This post was originally published at The Federalist.